South Africans are experiencing worsening power cuts as winter hits and the crisis fuels demands for political change in Africa’s most advanced economy.

Wiseman Bambatha was indulging in wishful thinking when he named his business Goodhope Saddlery.

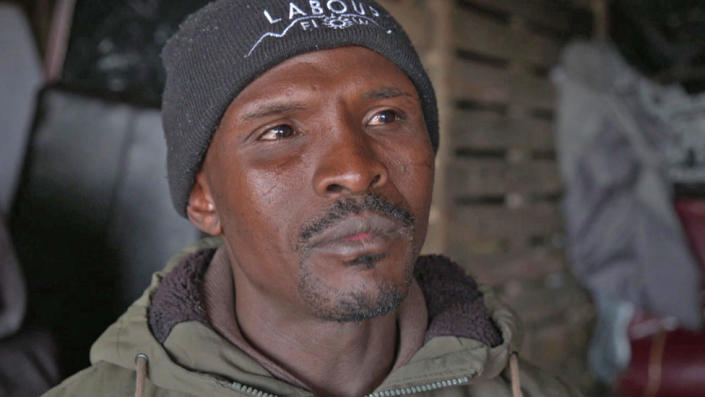

Mr Bambatha refurbishes sofas and chairs in a dingy one-room workshop in the sprawling township of Khayelitsha, on the outskirts of Cape Town.

But for hours, her dilapidated electric sewing machine sits idle. The power goes out in Khayelitsha for eight or 10 hours almost every day. In South Africa, we talk about load shedding.

Orders are not fulfilled, customers are angry.

Mr. Bambatha winces and admits his business is hanging by a thread. It’s a story that is being played out across the country.

In an already dysfunctional economy, with half of all young adults unemployed, shedding is a job killer.

“The government has been promising us a better life for years,” says Mr Bambatha, pacing his potholed street and a view of corrugated iron shacks beyond. “Tell me, where is he?”

Khayelitsha is home to over a million people. When night falls and the power fails, he is shrouded in eerie darkness, punctuated by streetside braziers.

Cape Town already had the dubious distinction of being Africa’s murder capital – load shedding and no street lighting added a new level of threat.

After sunset, I meet Mr. Bambatha’s wife, Ruby, huddled on a sofa with her two young daughters, all illuminated by a flickering candle.

“I always try to get home before dark, get the kids in and lock the door – only then do I feel safe,” she says.

And even in death, the crisis of power robs South Africans of their dignity.

Juggle with corpses

A man who runs a funeral home a few miles from Khayelitsha keeps bodies in cold storage behind his office.

“When the power goes out for four hours, we have a big problem,” he says. “The corpses are starting to decompose, you can imagine the smell. It’s not something the bereaved families can accept.”

So the funeral director calls his friends in the trade. When he finds someone who still has electricity and space in their cold room, he transports their bodies to them.

Across Cape Town, corpses are juggled every day in search of reliable food.

The load shedding looks like the service delivery failure that could break the African National Congress (ANC)’s grip on power.

The specific reasons for rolling breakdowns are legion: obsolete coal-fired power plants; incompetent management of the public energy company Eskom and endemic corruption.

But at the end of the day, there is a harsh political reality: Nelson Mandela’s party, which has monopolized power for 29 years since liberation from apartheid, owns this crisis.

I meet the ANC secretary general, Fikile Mbalula, five minutes after power and light return to Luthuli House, the party’s headquarters in Johannesburg.

He used to revel in the nickname “Mr Fixit”. No one seems to call it that now.

“Shedding could be our Achilles heel,” he admits with surprising candor. “It could cost us our majority.”

South Africans will go to the polls next year. Polls for the ANC and President Cyril Ramaphosa have been falling for months.

The party is vulnerable like never before, but only if voters have a credible alternative.

The leader of South Africa’s largest opposition party, the Democratic Alliance (DA), is John Steenhuisen.

His Cape Town office gives clues to the scale of his ambition. There are pictures of former US President John F Kennedy everywhere.

In another nod to his political hero, Mr Steenhuisen promises me that he will put together a “moon coalition” of a dozen opposition parties to bring down the ANC.

But Mr. Steenhuisen is white in a country where whites make up only 7% of the population. Two-thirds of his party members are white. The same goes for 70% of the faces in South Africa’s meeting rooms.

No amount of DA talk of competence and meritocracy can obscure the fact that South Africa is not a society that has left behind the trauma and systemic inequality of apartheid.

Which means that the most powerful political force in the country right now might just be Julius Malema.

He was kicked out of the ANC more than a decade ago – party bigwigs told him to take anger management courses following a series of accusations of inciting racial hatred and violence.

He founded his own party, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), committed to the nationalization of land, banks and mines – in other words, the essential pillars of residual white economic power.

Mr. Malema senses an opportunity as the energy crisis worsens this winter.

“Let the grid collapse,” he tells me. “I don’t wish it, but it’s going to happen, and then people are going to rise up – I’m telling you there’s going to be a revolution.”

The ANC has managed, or mismanaged, South Africa for the past 29 years.

Judgment day is fast approaching, and it promises to be painful.