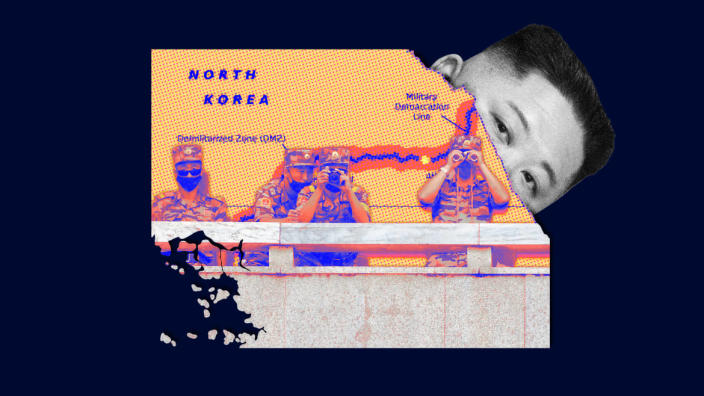

The “truce village” straddling the line between North and South Korea where the Korean War armistice was signed 70 years ago now looks more like a sieve than a barrier for anyone considering jumping across.

Oddly, it was North Korea’s caution that left them so exposed.

“There are no North Korean guards because of the COVID lockdown on their side,” said Victor Cha, who served as Asia director at the National Security Council when George W. Bush was president. Once Army private Travis King “takes a break,” Cha told The Daily Beast, U.S. and South Korean military guides “cannot chase after him,” that is, across the line north to the truce village of Panmunjom 35 miles north of Seoul.

In the face of rising tensions and threats of retaliation from both sides, the ease with which the disgruntled soldier entered North Korea reveals the weakness of what is supposed to be the world’s most heavily defended border between two hostile states.

“North Koreans have been almost invisible since COVID,” said Steve Tharp, a retired US Army officer who was often assigned to the JSA. He said they were rarely seen where they once stood by their side, sometimes muttering obscene insults to American and South Korean soldiers a few feet away.

When they appear, Tharp said, they are usually wearing hazmat suits to protect them from contamination by South Koreans, whom North Korea blames for spreading COVID on breezes blowing from south to north. North Korea closed its borders in early 2020 after COVID was first reported in China.

US soldier was ‘collapsed’ before rushing to North Korea, uncle says

“King just separated from the tour group and crossed the line into North Korea,” said David Maxwell, a former Army Special Forces colonel who has completed five tours of South Korea.

Unlike North Koreans, South Korean and American soldiers “will not chase or shoot a defector,” said Maxwell, now at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies in Washington. “Anyone intending to cross the military demarcation line in the joint security area could do so easily. The only thing that could be done was to put up a wall of guards or just cancel tours (which I’m sure have been done).

Evans Revere, former chief of mission at the US Embassy in Seoul, recalled that there was almost nothing to stop a determined bolter from crossing the line. “I’ve been to the JSA dozens of times,” he said. “Once you are present on Conference Row, there are no real obstacles to crossing over to the other side, if that is your intention.”

When Revere was based in Seoul, armed guards from both sides faced each other between aluminum-roofed structures built directly on the line. Under the comprehensive military agreement reached between North and South Korea four years ago, not only are the guards unarmed, but they no longer stand between buildings.

“There is no physical barrier,” Revere said. “There are several places on Conference Row where a determined person could easily walk away from the tour group.” It all depends on the willingness of the potential defector to expose themselves as a target for North Korean soldiers.

“Defecting to Panmunjom is risky,” said David Straub, who for years served as a political officer at the US embassy in Seoul and visited North Korea on official business. “The defector himself could be shot, and the defection is likely to trigger a firefight among the armed guards there.”

Still, Straub said, “a number of people on both sides have defected via Panmunjom over the decades because it’s less risky and requires far less knowledge and planning than crossing elsewhere in the DMZ”, i.e. the 2 1/2 mile wide demilitarized zone that stretches 154 miles across the peninsula where firing stopped on July 27, 1953.

Nowadays, since they are unarmed, American and South Korean soldiers in the Joint Security Area could not open fire even if they wanted to. The North Koreans are also not expected to carry arms, although it is unclear to what extent they are sticking to a deal that was meant to ease North-South tensions.

Tharp saw the danger of anyone defecting from South Korea to North Korea as having seemed so low that it had not been a serious concern until it happened.

“Because defecting to North Korea is not normal, it’s not a priority – until now,” he said. “All someone needs is the element of surprise and a small gap, and they can cross the line before they get caught.”

Cha, longtime director of Korea at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, said: “Tour groups are generally not allowed to walk to the military demarcation line, but are allowed to stroll to the United Nations side… That probably won’t be allowed anymore. One person ruins it for everyone.

Maxwell defended the American and South Korean record for providing security, at least outside of the JSA.

“The accusation that security is lax is simply not justified,” he said. “Neither South Korean nor American soldiers are looking for defectors. They are more concerned about the threats North Koreans pose to the people, even though they are now generally completely out of sight since COVID.

The DMZ’s southern barrier, he said, “is heavily guarded, has cameras, and is raking sand to reveal footprints.”

For North Koreans, he said, “the focus is on northern infiltrators, not southern defectors.” Maxwell remembers seeing a mine explode on the north side on Christmas Day 1987 while on a daylight reconnaissance patrol with his reconnaissance platoon.

For the U.S. and South Korean commands, however, King’s defection says a lot more about security on the South Korean side despite repeated threats from North Korean leader Kim Jong Un and his little sister Kim Yo Jong of nuclear attack and launching intermediate-range ballistic missiles capable of carrying nuclear warheads to targets in the United States.

US and South Korean border soldiers were “herding” on the group from which King suddenly defected, Tharp said. “The guards were following the tour,” he said, but obviously weren’t close enough to grab King after he laughed loudly and ran for the line.

No North Korean soldiers were visible on their side, but they presumably grabbed King when he reached the two-story building known as Panmungak, 100 meters inside North Korea.

Now, Tharp said, “tours will be shut down indefinitely” while Americans and South Koreans “do a review and come up with some changes” — no doubt in the form of posting more unarmed guards and vetting anyone who wants to join DMZ tours.

If they had bothered to check King, they would have discovered that he had been imprisoned in South Korea for assault and should have been flown to Fort Bliss, Texas, where he faced US military charges. After the US military police let him go to airport security, he snuck out of the airport and signed up for the Panmunjom tour.

Tharp doubted the North Koreans would release him, just as they never released other American soldiers who defected to the North.

Little sister takes charge as Kim Jong Un transforms into Vegas-era Elvis Presley

The last of the six to cross the North before King was Private First Class Joseph White, who North Korea says drowned in a river in August 1985, three years after defecting while on patrol several miles from Panmunjom.

King is the first American soldier to defect through the DMZ. The other six, including White, defected by leaving their patrols or bases, entering landmine-infested territory and breaking through the barbed wire barricade of the DMZ,

All the others are dead, most recently Charles Jenkins six years ago in Japan. Drunk on beer, he crossed the line while on patrol in 1965. Tortured and beaten, he was eventually allowed to marry a Japanese woman whom the North Koreans had abducted from a beach in Japan and who had been told to teach Japanese. She was sent back to Japan in 2002, and he and their two daughters were released two years later.

“Something like that obviously could cause an international incident,” said Bruce Bechtol, a former intelligence analyst in the marines in Korea and then at the Pentagon. Jenkins “basically went through the DMZ,” said Bechtol, author of numerous books and articles on North Korea’s military leadership. “The North Koreans ended up using it for propaganda purposes.”

The latest defection comes as the Americans and South Koreans step up joint military exercises amid escalating North Korean rhetoric. The USS Kentucky nuclear submarine, docked in the port of Busan, is the first nuclear submarine to visit South Korea since 1981. The incident also coincides with a meeting in Seoul of the newly formed nuclear advisory group in which Kurt Campbell, the Indo-Pacific coordinator of the National Security Council, is leading a large delegation, raising speculation about the negotiations.

Colonel Maxwell doubted that the North Koreans would succeed in using King’s defection as a negotiating tool. “We will not back down or make any concessions to the North,” he told the Daily Beast. “There will be no such negotiation with a concession such as sending the submarine in exchange for the soldier.”

He thought, however, that the North Koreans and the Americans could start talks. “If the KPA doesn’t pick up the phone at the JSA,” he said, “the UNC side will broadcast with a megaphone asking for a meeting.”

Maxwell predicted that Smith’s defection could at most serve briefly for propaganda purposes as tensions mount on the Korean peninsula. Pfc. White “was used for propaganda for a time but later died,” Maxwell said. “A similar fate likely awaits PC1 King.”

“It’s not going to be resolved any time soon,” Victor Cha told The Daily Beast. “North Korea will maximize the value of propaganda. In the past, detainees have been held for weeks or even months, sometimes with a show trial, sentencing, and then a forced apology. Someone usually has to go get their release too. The only silver lining is that NK will have to answer the Biden administration’s phone to resolve this issue, which they have been unwilling to do so far.

Learn more about The Daily Beast.

Get the Daily Beast’s biggest scoops and scandals straight to your inbox. Register now.

Stay informed and get unlimited access to The Daily Beast’s unrivaled reports. Subscribe now.